Chinese Works of Art

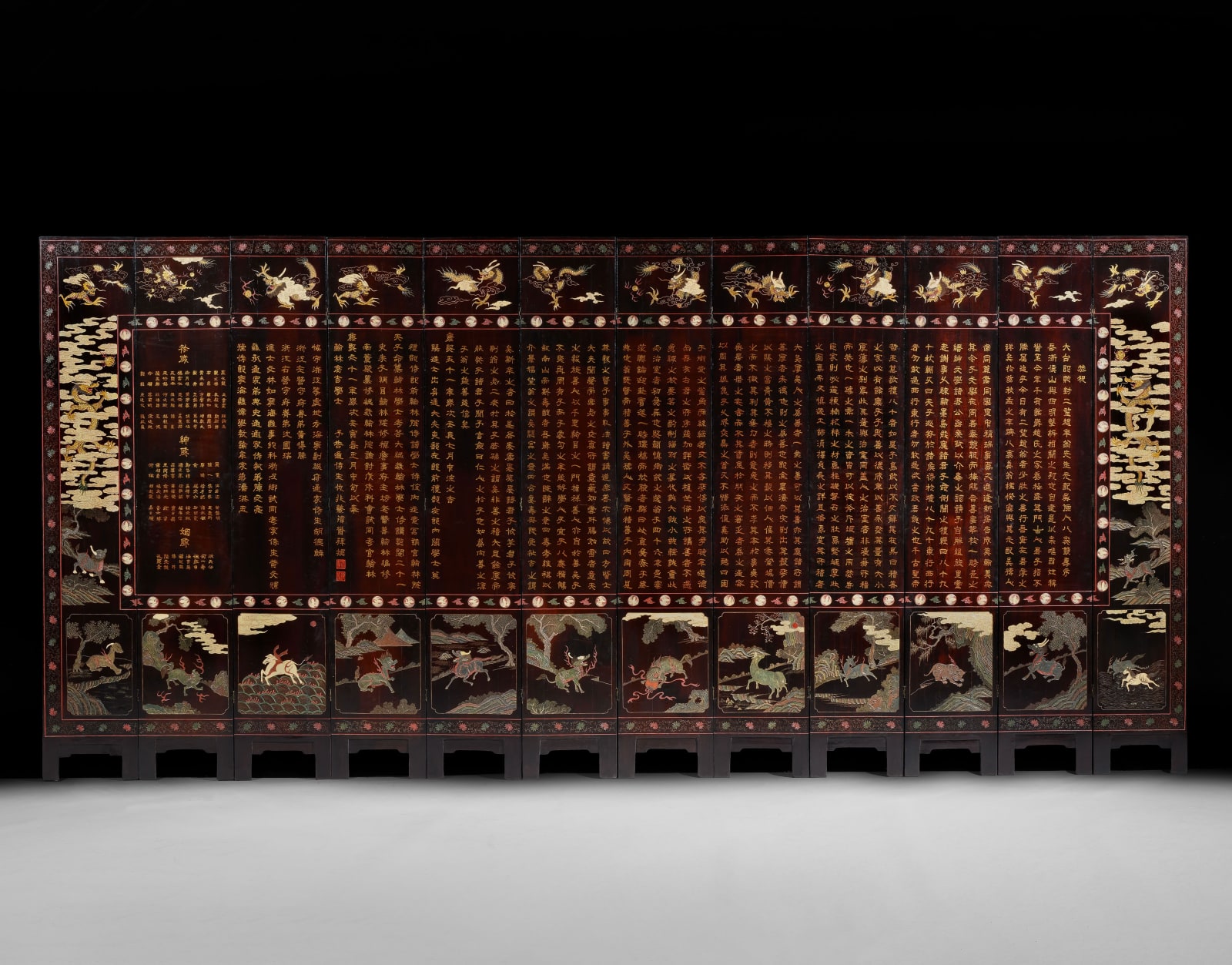

A Magnificent Twelve-Panel Coromandel Lacquer Screen Depicting Guo Ziyi

Width: 19ft 5.76 m: (Each panel: 19” 55 cm)

Further images

Provenance

The property of a notable French family, by whom acquired in 1935

Exhibitions

Compare

Cernuschi Museum, Paris: Identical example depicting Guo Ziyi’s birthday celebration in a palace setting, though Cernuschi example is lacking the inscription to the front as on the present example.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: A Coromandel twelvefold screen showing a continuous palace scene on the front and still-life and landscape motifs on the reverse

Auction: Example formerly in the collection of A. Jerrold Perenchio, sold Christie’s, 16th September 2020, USD $212,500. Example in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, USA (no. B69M52Literature

de Kesel, W & Dhont, G., Coromandel Lacquer Screens (New York, 2002), esp. pp. 32-57

A Magnificent Twelve-Panel Coromandel Lacquer Screen Depicting Guo Ziyi

Kangxi Period, Dated to the 61st Year of the Kangxi Reign (1722)

Description

This exceptional twelve-panel screen is a superb example of Coromandel lacquer, known in Chinese as kuancai (“incised colours”). Combining monumental scale, narrative richness, and remarkable preservation, it presents on one side a palace scene depicting the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi surrounded by attendants, courtiers, and mounted horsemen. The reverse bears a dedicatory inscription dated to the 61st and final year of the Kangxi reign (1722), recording its commission as a birthday gift for a high-ranking official.

Obverse: Guo Ziyi and the 1722 Historical Context

The front of the screen portrays Guo Ziyi (697–781), revered for his loyalty, military brilliance, and service under four emperors. Credited with saving the Tang dynasty by quelling the An Lushan Rebellion and later deified as a god of wealth and happiness, Guo became a potent emblem in Ming and Qing visual culture. Depictions of his later years, surrounded by family and attendants, symbolised loyalty, longevity, and dynastic stability.

Here, Guo is shown receiving guests in a sumptuous palace setting attended by officials, musicians, servants, and mounted guards, with tiered pavilions, winding garden paths, bridges, and decorative screens evoking the grandeur of the Tang court. The residence of the general unfolds in rich detail: a procession approaches from the right to present tribute to the master enthroned in the central pavilion, while to the left the women’s quarters are depicted with equal narrative complexity. This iconography of Guo Ziyi’s birthday reinforced themes of prosperity, order, and dynastic continuity.

The choice of subject was especially resonant in 1722, the final year of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign, one of the longest and most celebrated in Chinese history. Commissioned at this moment of dynastic transition, just before the accession of the Yongzheng Emperor, the screen can be read as both a personal tribute and a political statement of loyalty and stability.

Coromandel Lacquer Technique and Trade Context

Coromandel lacquers take their name from the east coast of India, where they were landed from Chinese junks to be transferred to ships of European trading companies. These works, often produced in China as prestigious gifts for high dignitaries, were widely imported into Europe from the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722). Upon arrival, they were incorporated into wealthy homes or dismantled to be reused as decorative panels by leading furniture makers.

Coromandel lacquer emerged in China during the 16th century and ranks among the most technically accomplished lacquer techniques of the late Ming and Qing dynasties. The process involved a wooden frame covered with fabric and successive layers of lacquer, a vegetable resin that polymerises on contact with air. The decoration was then incised in hollow, with the contours left in relief, and painted with red, blue, green, and white pigments that contrast vividly with the polished lacquer ground, typically brown to black.

Despite its name, “Coromandel lacquer” was not produced in India. The term arose because screens made in southern Chinese workshops, particularly in Guangdong and Fujian, were shipped to Europe via the Coromandel Coast of India, a key maritime trade hub. European collectors, unfamiliar with their true origins, adopted the misleading designation.

It was long assumed that large kuancai screens were produced primarily for export to Europe, where they were highly prized. Recent scholarship, however, shows that while some examples were indeed made for elite European patrons, many were created for the domestic Chinese market, where they carried equal or greater prestige. In the 17th and 18th centuries, European craftsmen, responding to the vogue for Chinese design, often cut screens down for use as panels in cabinets and commodes, notably in commissions by André-Charles Boulle in France and Thomas Chippendale and James Moore in England. Others were preserved intact and installed in grand European interiors, including the Chinese Cabinets at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm in Sweden, and the Chinese Room of the Palazzo Averoldi in Brescia. By the 20th century, Coromandel screens had become icons of cosmopolitan taste, most famously employed by Coco Chanel as dramatic wall panelling in her Paris apartment.

Symbolism and Reverse

The decoration is rich with auspicious symbolism. Surrounding Guo are bogu (precious objects)—vases, archaic bronzes, musical instruments, scrolls, and scholarly implements—signifying erudition, refined taste, and moral cultivation. Floral motifs such as peonies (wealth), chrysanthemums (endurance), prunus blossom (purity), and lotus (enlightenment) reinforce these blessings, while cloud scrolls and layered mountains draw on Daoist imagery to link earthly order with cosmic harmony.

The reverse bears a poetic inscription in gilt, commemorating the presentation of the screen in Kangxi’s 61st year as a birthday gift to a senior military official. Such inscriptions often list the donors who contributed to the commission, underscoring both the prestige of the recipient and the collective act of loyalty embodied in the gift. Around it, twelve auspicious creatures including cranes, deer, phoenixes, qilin, and the ba jun (“Eight Horses”), form a symbolic cycle of protection, prosperity, and good fortune, possibly alluding to the twelve lunar months or earthly branches. Together, the obverse and reverse form a unified statement of loyalty, virtue, and enduring prosperity.

Rarity and Significance

The survival of a twelve-panel kuancai screen of this date, with both narrative and inscriptional sides intact, is very rare. The precise date (1722), the Guo Ziyi subject, and the superb quality of its execution place this example among important Kangxi-period Coromandel screens. Its monumental scale, rich iconography, and exceptional preservation establish it as a masterwork of lacquer commissioned in the final year of Kangxi’s reign, an emperor whose patronage defined the material and visual culture of the Qing court and beyond.