Chinese Works of Art

A PAIR OF CARVED SOAPSTONE FIGURES OF A MANDARIN AND FEMALE ATTENDANT

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

Provenance

The collection of Mr Basil (1884-1950) and the Hon. Mrs Nellie Ionides (1883-1962), the Library at Buxted Park, Sussex

By descent to Lady Camilla Panufnik, née Jessel, (b.1937), who married renown symphonic composer, Andrzej Panufnik

Literature

F. Gordon Roe, ‘A Chinese Craft: Chinese Soapstone Carvings’, The Connoisseur (London, 1920), pp. 157-61

Publications

R. Soame Jenyns, Chinese Art: Textiles – Glass and Painting of Glass – Carvings in Ivory and Rhinoceros Horn – Carvings in Hardstones – Snuff Bottles – Inkcakes and Inkstones (2nd ed., rev. William Watson) (Oxford, 1981), p. 208, fig. 181

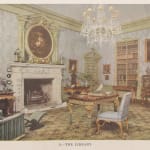

Hussey, Christopher, ‘Buxted Park, Sussex – II, The Home of Mr. and the Hon. Mrs. Basil Ionides’, Country Life (11th August 1950), p. 445, fig. 8, the Library, showing the figures in situ

An Exceptional and monumental pair of Kangxi Soapstone Court Figures

Chinese: Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

This extraordinary pair of large Kangxi period (1662–1722) soapstone figures, depicting a mandarin of the highest civil rank and a female companion represents a unique and masterfully executed expression of Kangxi Chinese sculpture. Their large scale, secular subject matter, and exceptional state of preservation distinguish them from all other surviving Chinese soapstone carvings, which typically depict sacred figures such as Guanyin, luohan, or Daoist immortals, or are small-scale seals incorporating mythological beasts. These figures stand apart as a rare secular and courtly portrayal; deeply human, formally complex, and stylistically refined.

Carved from veined and variegated soapstone, a material prized for its softness and painterly surface, these figures were likely intended as prestigious diplomatic or courtly gifts, or as commissions for an elite domestic setting. The presence of such secular imagery, especially on this scale, suggests an intended audience familiar with the civil hierarchy and visual culture of the imperial court. These were not votive or devotional figures; they were statements of status, taste, and cosmopolitan refinement.

The mandarin is shown wearing a formal court robe incised with dragons, crashing waves, and floating clouds, symbolising both imperial association and scholarly authority. His buzi, or rank badge, features a crane denoting the highest (first) rank of civil official. This is not simply a generalised figure, but one deeply embedded in Qing political and social iconography. The care taken in articulating the folds of his robe, the fluidity of his posture, and the nuanced rendering of his facial expression—all contribute to a portrait of dignity, restraint, and intellectual presence. His hand gestures convey naturalism and narrative potential.

The female figure, possibly his wife or attendant, is modelled with a flowing robe painted in tones of ochre, coral, and green, and finely incised with stylised cloud scrolls, floral roundels, and symbolic plants. Her distinctive gaoliang hairstyle, with hair swept into a high, wide chignon secured over a transverse wooden frame, identifies her as a married Manchu woman. Unlike the stylised forms common to Buddhist or Daoist sculpture, her softly tilted head, almond-shaped eyes, and demure gesture embody a subtle psychological realism.

The artistry on display is remarkable. The soapstone has been carved and polished with extraordinary finesse, then enriched with layers of mineral pigments and gold to evoke the sumptuous textures of silk embroidery and ceremonial regalia. The contrast between the smooth finish of the skin and the dense, rhythmic incisions of the clothing showcases the carver’s deep understanding of material and form. Achieving this degree of detail and expressive subtlety in such a friable and soft medium required not only great technical skill but careful planning and a masterful sense of composition.

Formerly in the celebrated collection of Mr Basil Ionides (1884–1950) and the Hon. Mrs Nellie Ionides (1883–1962), these figures were displayed in the Library at Buxted Park, Sussex ( see image) an early 20th-century English interior renowned for its rich assemblage of Chinese and European decorative arts. The Ionides family were discerning collectors and tastemakers whose interest in early Qing material placed them among the foremost British patrons of Chinese art.

In scale, subject, craftsmanship, and provenance, this pair stand without parallel. Their survival attests not only to the virtuosity of Kangxi period artisans but also to the status of the individuals for whom they were commissioned. More than sculptures, they are embodiments of the refined culture, cosmopolitan sensibility, and artistic excellence that defined the high Qing court.