WORKS FOR SALE

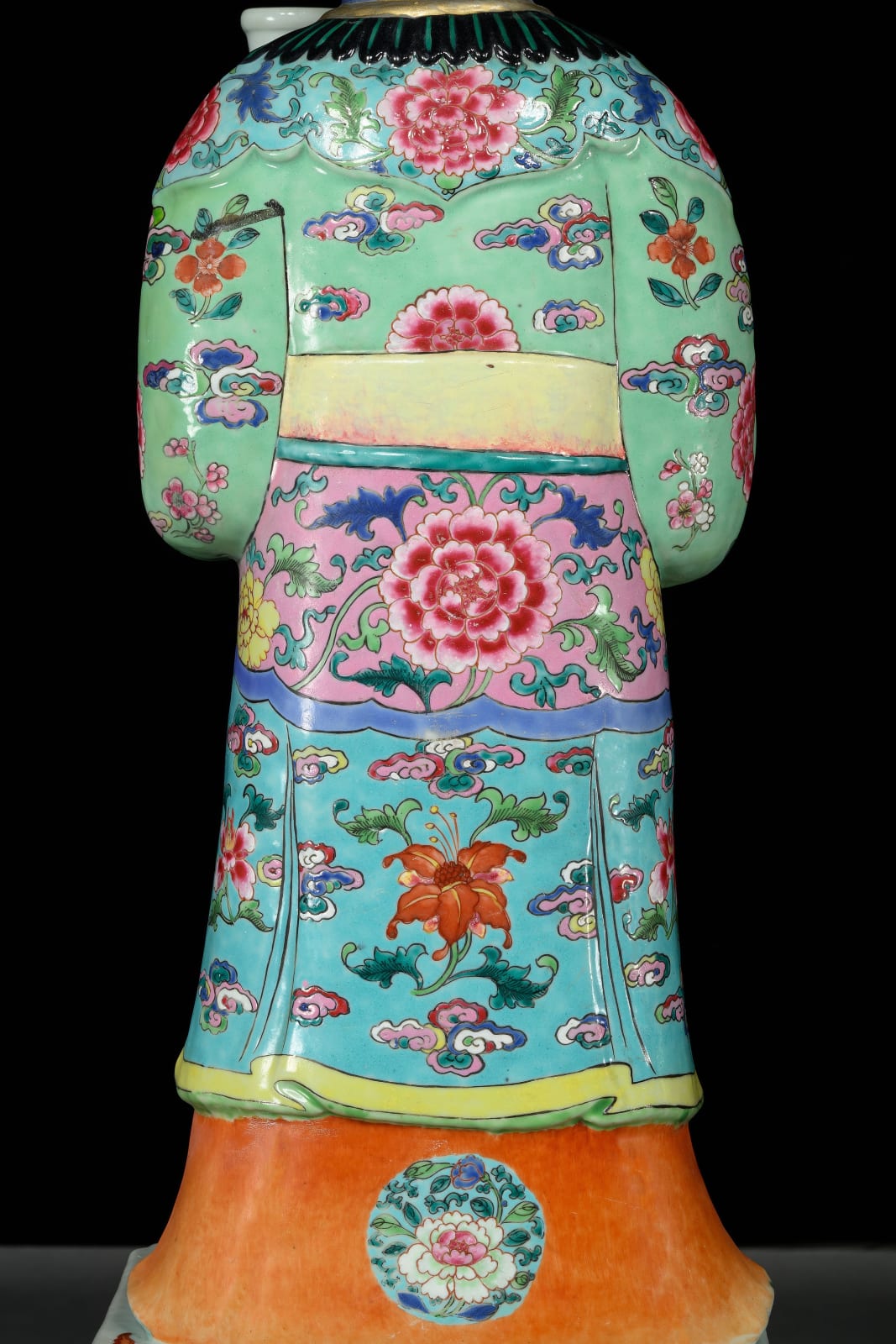

GROUP OF FOUR FAMILLE ROSE FIGURES OF TWO LADIES AND TWO BOYS

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

Provenance

Private Collection of the Societe Industrielle de Mulhouse, since early 20th century

Literature

COMPARE:

Galerie Gorges Petit, Objets d’Art Et d’Ameublement, Porcelaines De Chine (1914), pl. 104, for figures of a boy and lady of identical form and decoration

Edgar Gorer and J. F. Blacker, Chinese Porcelain and Hardstones, vol. II (1911), pl. 229, for a comparable boy and lady pair from the R. Bennett collection

Palace Museum in Gotha, Germany, c.f. the exhibition catalogue Schätze Chinas aus Museen der DDR, eds. H. Bräutigam, A. Eggebrecht, the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim 8 April - 15 July 1990, nos. 224-5, two famille verte figures of boys

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, USA, illustrated W. R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (Massachusetts, 2012), p. 459-61, cat. no. 255, for a figure of a boy, also David S. Howard, A Tale of Three Cities (London, 1997), p. 135, fig. 171, and exhibited, sold Sotheby’s, 17 November 1999, lot 982, USD 188,917

Lady Lever Gallery in Liverpool, England, illustrated by R. L. Hobson in his Catalogue (1928), pls. 75-6 and Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 35 (1963-4), p. 65, no. 228, another boy and lady pair

Collection of Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva (formerly), illustrated Mary Lobo Antunes, Chinese Porcelain: Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva Collection (Lisbon, 2000), p. 31, no. 9, and Maria Antónia Pinto de Matos, Porcelena Chinesa: De Presente Régio a Produto Commercial (Lisbon, 1998), p. 318-19, no. 124, for another boy pair

A Rare and Exceptional Group of Four Famille Rose Figures of Two Ladies and Two Boys

China, Qing Dynasty, Yongzheng (1722–35) – Early Qianlong Period (1736–95), circa 1730–40

Exquisitely modelled and richly enameled in famille rose palettes, this rare group of four porcelain figures—two court ladies and two boys—embodies the refinement, symbolism, and vibrant aesthetic of Qing courtly taste at its most sophisticated. Each figure stands on an elaborate original pedestal, creating an ensemble of remarkable completeness and scale.

The two ladies are dressed in finely detailed robes, adorned with vivid floral ornament including plum blossoms—emblematic of the Five Blessings (longevity, wealth, health, virtue, and peaceful death)—and prominently, lilies (baihe). Through a phonetic rebus, the lily symbolises “harmony and unity” (hehe), making the figures especially appropriate as nuptial gifts. The phrase bainian haohe (“happy union for one hundred years”) was commonly associated with such imagery, as were orange lilies, which signify passionate love.

The two boys, with joyful expressions and lively gestures, wear robes decorated with lotus blooms and phoenix motifs. The lotus (he) is a homophone for “harmony” and, in its variant lian, also means “continuous,” conveying wishes for abundant children and enduring familial prosperity. One boy’s robe displays a profusion of lotus stems and blooms, further referencing the Chinese word ou—a pun for both “lotus root” and “married couple.” The symbolism is reinforced through the boys’ phoenix medallions, coloured in the five Confucian virtues: benevolence, righteousness, propriety, knowledge, and sincerity.

These figures reflect traditional beliefs surrounding childhood and protection. The boys’ earlobes are pierced, as were those of living male children, to accommodate earrings intended to deceive spirits who targeted boys but spared girls. Similarly, gold locks and bracelets made from coffin nails were worn to bind boys to the family and deter evil. The cheerful bearing of these boys, however, reflects their fortunate status and spiritual security.

The symbolism continues on the hexagonal pedestal bases. Each is decorated with phoenixes and peonies—representing beauty, rank, and material wealth—as well as pierced roundels in the shape of sapeca coins (zhu), invoking prosperity. Morning glories, associated with romantic longing and conjugal bliss, further reinforce the nuptial message. Between their feet, the boys carry peony-filled pouches, meant to secure and protect their future abundance and fertility.

As H. Bräutigam has noted, this specific combination of iconography—particularly the lotus, vase (ping), and lily—expresses the rebus hehe meiping, or “harmonious and peacefully united.” This linguistic and visual metaphor, rendered in such technically and materially costly porcelain, suggests that figures of this kind were likely intended for presentation at aristocratic marriages.

The level of technical refinement, brilliant palette, and complexity of the symbolism all point to a production in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province—the centre of imperial porcelain manufacture from the Yuan dynasty onward. By the 1730s, under the Yongzheng emperor and continued into the early Qianlong reign, Jingdezhen was producing exceptionally high-quality wares, both for domestic elite consumption and export.

Though the present figures were likely made for export, their level of workmanship suggests they were likely commissioned for a prominent household, possibly even for presentation to an overseas dignitary or wealthy European merchant. The carefully composed iconography, the delicacy of facial expression, and the perfectly balanced enamels would have required skilled artisans and specialist decorators operating under supervision, perhaps even from workshops that contributed to both imperial and private production. The figures’ hollow but sturdy construction and painted base panels suggest a convergence of sculptural technique with the decorative standards of porcelain wares.

Figures of this type, particularly of this scale (each figure over 60cm high including the plinth), required multiple firings and meticulous painting using the new yangcai (foreign colour) technique—what the West called famille rose. The rich enamelling, visible especially in the detailed floral work on the robes and pedestals, would have been applied over the glaze, then fired at lower temperatures in muffle kilns, demanding precise control and careful handling throughout the process.

The survival of a matched group of four is virtually without precedent. While pairs of a boy and lady figure are recorded in several major collections—including those of Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva, the Lady Lever Art Gallery, and the Peabody Essex Museum—complete quartets are extremely rare. Figures of this size and fragility, often exported in the 18th century across great distances, would frequently become separated, damaged, or lost over time. This complete, unified group—retaining their original pedestal bases and extraordinary colour—is likely one of the only known surviving sets of its kind.

The figures were probably conceived as an allegorical tableau representing harmony (和), union (合), prosperity, and familial continuity, intended to celebrate or commemorate an elite marriage. The ensemble’s iconography, scale, and expense would have made it suitable for prominent display in a reception hall or bridal chamber—whether in China or abroad—and its symbolic meanings would have been legible both to Chinese and well-informed European audiences.

Each figure carries auspicious attributes—lotus, lilies, peonies, phoenixes, morning glories, and the sapeca coin motif—woven into a sophisticated visual rebus. As H. Bräutigam

Comparative Examples

This group belongs to a rare and esteemed category of export figures, preserved in only a handful of private and institutional collections worldwide:

-

A lady and boy with nearly identical decoration appear in Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement, Porcelaines De Chine (1914), pl. 104, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris.

-

Another pair was in the collection of R. Bennett, illustrated in Gorer and Blacker, Chinese Porcelain and Hardstones, Vol. II (1911), pl. 229.

-

Two famille verte boys are held in the Palace Museum, Gotha, Germany (see Schätze Chinas, 1990, nos. 224–5).

-

The Lady Lever Gallery in Liverpool houses a comparable pair, illustrated in R. L. Hobson’s Catalogue of the Chinese Porcelain in the Lady Lever Art Gallery (1928), pls. 75–6.

-

An almost identical boy (missing its base) appeared in A Tale of Three Cities (1997), later sold at Sotheby’s (17 Nov 1999, lot 982) and now in the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem (see William R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics, 2012, cat. no. 255).

-

A fine pair of boys was formerly in the Collection of Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva (see Mary Lobo Antunes, Chinese Porcelain, 2000, p. 31, no. 9).

Rare in both scale and completeness, and distinguished by their exceptional modelling, original bases, and remarkably preserved enamels, these figures epitomise the symbolic richness and artistic excellence of high Qing porcelain. Their unique combination of auspicious motifs and courtly elegance strongly suggests they were commissioned for an elite domestic context—likely a wedding—where they would have conveyed hopes for harmony, fertility, and enduring fortune.