WORKS FOR SALE

AN ENAMELLED PORCELAIN MODEL OF A WOLF

Length: 38cm 15”

Further images

Provenance

Jakob Goldschmidt, Berlin, later New York, sold 1938

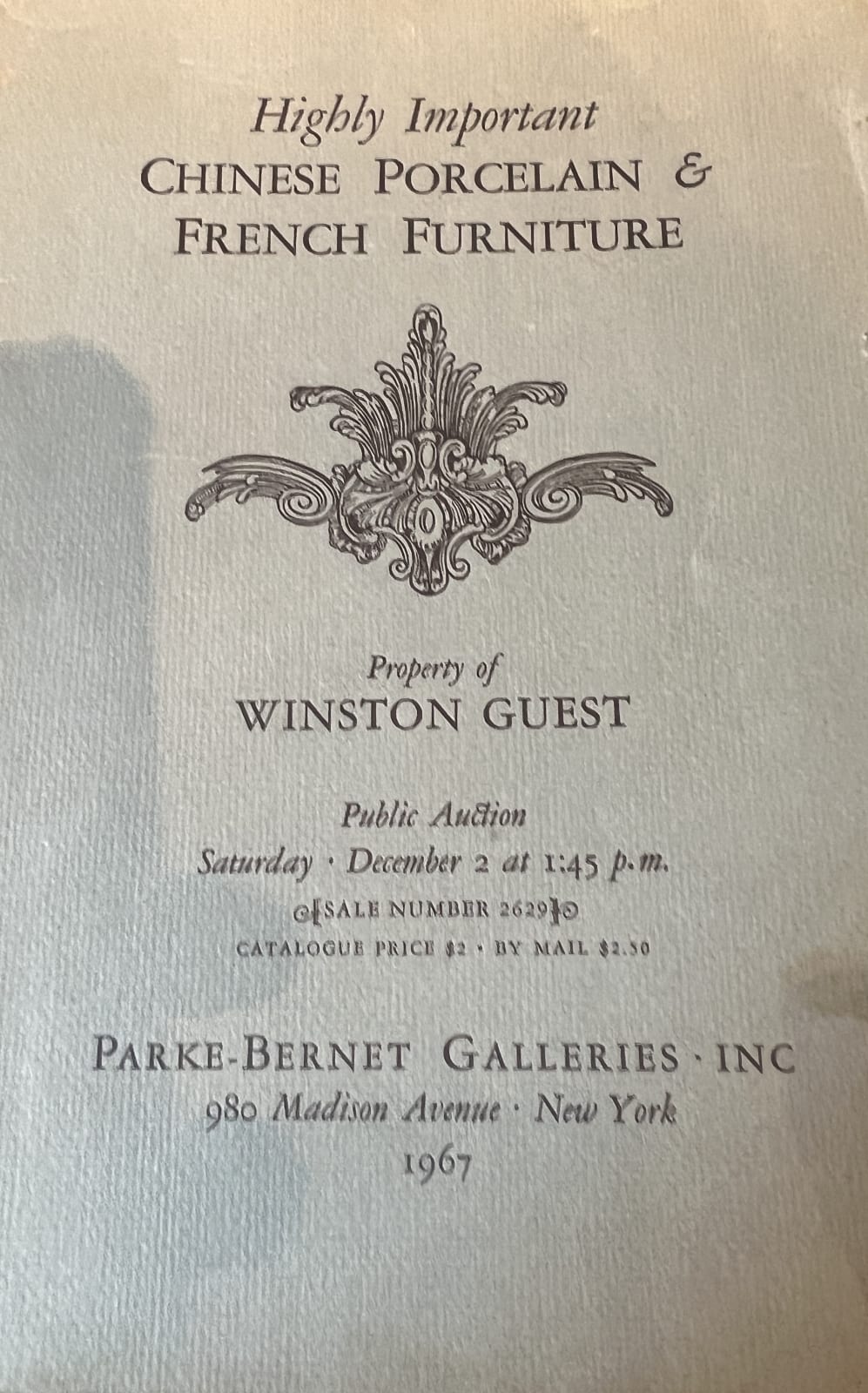

The Collection of Winston Guest, New York, sold Sotheby's Parke-Bernet, New York, 2 December 1967, lot 53

John Dorrance, Pennsylvania, sold 1997

Exhibitions

Berlin, Chinesische Kunst, Preußische Akademie der Künste, January - April 1929

Literature

Ayres, John. The Chinese Porcelain Collection of Marie Vergottis. Athens: Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art, 2004.

Noteworthy for figural pieces and rare export subjects in elite European collections.

Pierson, Stacey (ed.). Chinese Ceramics: The Sir Percival David Collection. London: British Museum Press, 2009.

- While focused on imperial wares, it offers important insight into technical developments that underpinned export production.

Jörg, Christiaan J.A. Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam:

- Includes a number of figural and animal porcelains made for export, with comparative pieces.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties. London: Philip Wilson, 1997.

Kändler, Johann Joachim. Meissener Porzellanplastik: Die Tierplastiken des 18. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Hirmer Verlag, various editions.

- Kändler’s menagerie is a key source of inspiration for Chinese export animal models. Many sculptures closely resemble Meissen prototypes.

Howard, David S. The Choice of the Private Trader: The Private Market in Chinese Export Porcelain Illustrated from the Hodroff Collection. London: Zwemmer, 1994.

- Includes a number of animal figures and discusses how Western market demands shaped Chinese production.

Compare:

Example illus. Cabinet Portier, 100 Ans: 1909 - 2009, fig. 321

Publications

Chinesische Kunst, Berlin, 1929, p. 348, fig. 948, described in the Meisterwerke Chinesische Kunst, as part of a summary of the above exhibition, no. 138

A rare Chinese export porcelain figure of a fox or wolf

Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period - Jiaqing Period c. 1730–1820

Realistically sculpted in the round, this striking porcelain figure stands alert on all fours, its body gently arched and head turned toward the viewer in a moment of lifelike engagement. The open mouth, with delicately rendered teeth and tongue, conveys a vivid expression—part growl, part curiosity—while the pricked ears heighten the impression of awareness. Its coat is finished with a lustrous amber-brown glaze, accented by darker streaks and subtle incisions that mimic the natural texture of fur. The cream-toned underside and muzzle, along with the blackened ears and finely detailed eyes, contribute to its powerful sense of animation and realism.

This rare and highly important figure is an exceptional example of Chinese porcelain produced specifically for the export market during the Qing dynasty. Its subject—the fox or wolf—is extraordinarily unusual within the canon of Chinese decorative arts, where such animals held little symbolic weight. Unlike dragons, lions, or horses, canines of this kind were virtually never represented in imperial or domestic wares. Their appearance here points directly to European influence and demand, most notably from Germany and other regions where lifelike animal sculpture—particularly by the Meissen manufactory—was highly prized.

By the early Qing period, especially under the Kangxi (1662–1722), Yongzheng (1723–1735), and Qianlong (1736–1795) emperors, the porcelain kilns at Jingdezhen were producing increasingly sophisticated wares specifically for export. Among these, naturalistic animal figures such as this one represent a fascinating fusion of Chinese technical virtuosity and Western aesthetic ideals. The influence of Meissen is particularly evident in the figure’s dynamic posture and the meticulous treatment of its surface—features that reflect a close study of European models, likely conveyed via engravings, sketches, or physical prototypes.

Unlike native Chinese animal figures—often more stylised and symbolic—export porcelains such as this were sculpted with a deep sensitivity to natural form and movement. Artisans lavished attention on anatomical precision, expressive gestures, and the layering of coloured glazes to simulate living texture. Rendered fully in the round, these works were intended to be viewed from all angles and displayed prominently, often as part of elaborate mantel or cabinet arrangements in European interiors.

Porcelain wolves or foxes of this calibre and scale were made in extremely limited numbers. Few survive today, and even fewer of this quality, presence, and condition. Their production required great skill and bespoke attention, likely commissioned for an elite clientele with a taste for exoticism and naturalistic form. As such, this figure stands among the most compelling and rare examples of Qing export animal sculpture known to exist. It would have served as a singular conversation piece within a grand collection, valued not only for its unusual subject and technical achievement but also for its role in the broader story of East–West artistic exchange.

The present figure boasts a particularly distinguished provenance. It was once in the celebrated collection of Jakob Goldschmidt, a prominent banker and collector in Berlin, later New York, and was sold in 1938. It subsequently entered the famed collection of Winston Guest, a noted New York society figure and descendant of the Duke of Marlborough, and was sold at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet, New York, on 2 December 1967, lot 53. Later, it formed part of the legendary collection of John Dorrance Jr., heir to the Campbell’s Soup fortune, and was sold in 1997. This exceptional chain of ownership further underscores the rarity and enduring appeal of this remarkable work of Qing dynasty porcelain.